2018 Goals Update

Books read: 23

Words on LIBRARIUM: 4,646/4,646 (It's finally dONE THANK GOODNESS)

Words on BRUSHSTROKES: 1,020/? (probably around 80-85K)

I finally feel like I'm back in the saddle as far as writing goes. The last couple of weeks have been lackluster as far as my creative work--day job stuff has taken up more of my time and I've, frankly, been lazy and distractable.

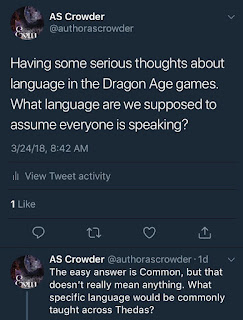

One of the things I've been doing while not getting words on the page is playing Dragon Age: Inquisition (which is my least favorite of the DA games, but we no longer have a working controller for our Xbox 360, so it's the only option right now).

For those unfamiliar, Dragon Age is a series of fantasy role playing games (we know how I love my RPGS) set on the fictional continent of Thedas. This is, in general, a meticulously crafted world. The various nations each have their own history and sets of relationships and political structures. Each location has its own architectural style and fashion, its own set of norms and hobbies. It really is spectacularly well thought-out.

Except for one thing.

Language is one of the aspects of world building that I don't think gets the attention it deserves. And I guess, in some ways, I get it. Not all of us are Tolkien. Most of us don't particularly want to sit down and create an entire fictional language (you don't actually have to do that to have quality language world building--but I'll get to that later).

It's pretty easy to wave away language in settings that involve multiple countries or planets by saying that everyone speaks "Common"--I mean, that's the one language that your character automatically knows D&D. But just saying that there's a shared tongue ignores the way that language intertwines with history and politics.

Basically, a language doesn't just become common. It's a process that's wrapped up in economic and colonial relationships.

Allow me to get sociological for a minute.

What are some of the situations where a language becomes widespread? Which of our fictional nations' languages would be the one most likely to be picked up and used in other countries?

The languages of colonial powers tend to be more widespread. English is spoken around the world in no small part because for a while the English national pass-time was sailing around the world, conquering nations and making the native peoples speak and behave in an Anglicized manner. England's not the only example--the story of how Spanish became the dominant language in so many Central and South American nations is pretty similar. What nations or world in your fictional setting have the itch to claim land in other nations or on other planets? The colonized often have to learn the language of their colonizers. Which language is "common" will in some ways be a matter of which nation has power.

Trade will also have an impact on what languages people learn. Which nation holds the economic power? Who controls the shipping lines? If you want to make money--if you want to be able to trade with other nations, to expand your markets--you have to learn that nation's language. Again, power is at play. The nation (or group or whatever) that controls the trade lines doesn't need to learn others' languages because they are the folks you have to go through to make money. They're needed and as such they can dictate terms. Learn our language if you want access. Take it or leave it.

It seems like such a little thing, but something as simple as what language is most commonly spoken can add so much detail to a fictional world. Ignoring this part of world building pokes a hole in your world's history.

Now, when it comes to fictional languages--I definitely get the unwillingness to craft an entire language. I know some basic structural things about my alien species' languages in my space opera, but I don't have a dictionary or anything like that. But I don't necessarily need to have one. I wrote the whole book, even scenes that are spoken in one of the fictional languages, in English. With a few hints, the reader can assume what language is being spoken.

Movies do this all the time. US adaptations for Les Miserables, for instance, are typically scripted in English, but we don't assume that all of these 19th century French folks are actually speaking English. The same idea can apply for a fictional language. An author can drop some clues--mention the setting and origins of the characters, say something about the familiarity of a language or if someone struggles to find a word, or even flat out say that someone is speaking in a particular language--to plant the idea of what language is being spoken in the reader's mind. No need to come up with a new language. Unless you just want to.

Every aspect of your world is a chance to make the reader's experience of it more complete. Language is no exception.

So, maybe take some extra time to think about who's speaking what and why.

No comments:

Post a Comment